learning-dynamics

syntax learning dynamics in MLMs

This is work that was completed with Jack Merullo and Michael Lepori on route to publication. It was conduected at the Brown University Lunar Lab under supervision of Ellie Pavlick.

Developmental Narrative of Syntax in MLMs

Discovering the “push-down effect”: how syntactic knowledge migrates from late to early layers during training, and what this reveals about in-context vs. in-weights learning strategies in masked language models

Where Does Grammar Live in MLMs?

When BERT processes the sentence “I will mail the letter,” how does it know that “mail” is functioning as a verb rather than a noun? Previous research has shown that language models develop sophisticated syntactic understanding, but a fundamental question remained unanswered: How do these representations develop during training?

Our research reveals a surprising phenomenon we call the “push-down effect”: syntactic information initially appears in later layers of the network but gradually migrates to earlier layers as training progresses. This migration tells a deeper story about how language models balance two competing strategies for understanding language.

Two Strategies for Understanding Language

Language models can represent syntactic information through two fundamentally different approaches:

In-Context Learning: The Algorithmic Approach

- Strategy: Derive part-of-speech information from surrounding context

- Example: “mail” after “will” → must be a verb

- Advantage: Handles ambiguous words flexibly

- Location: Typically requires deeper network layers for contextual reasoning

In-Weights Learning: The Memorization Approach

- Strategy: Encode part-of-speech information directly in word embeddings

- Example: “sofa” → almost always a noun, store this in the embedding

- Advantage: Fast, direct lookup for unambiguous words

- Location: Can be accessed from shallow network layers

The Central Question: When and why do models choose one strategy over the other?

Discovering the Push-Down Effect

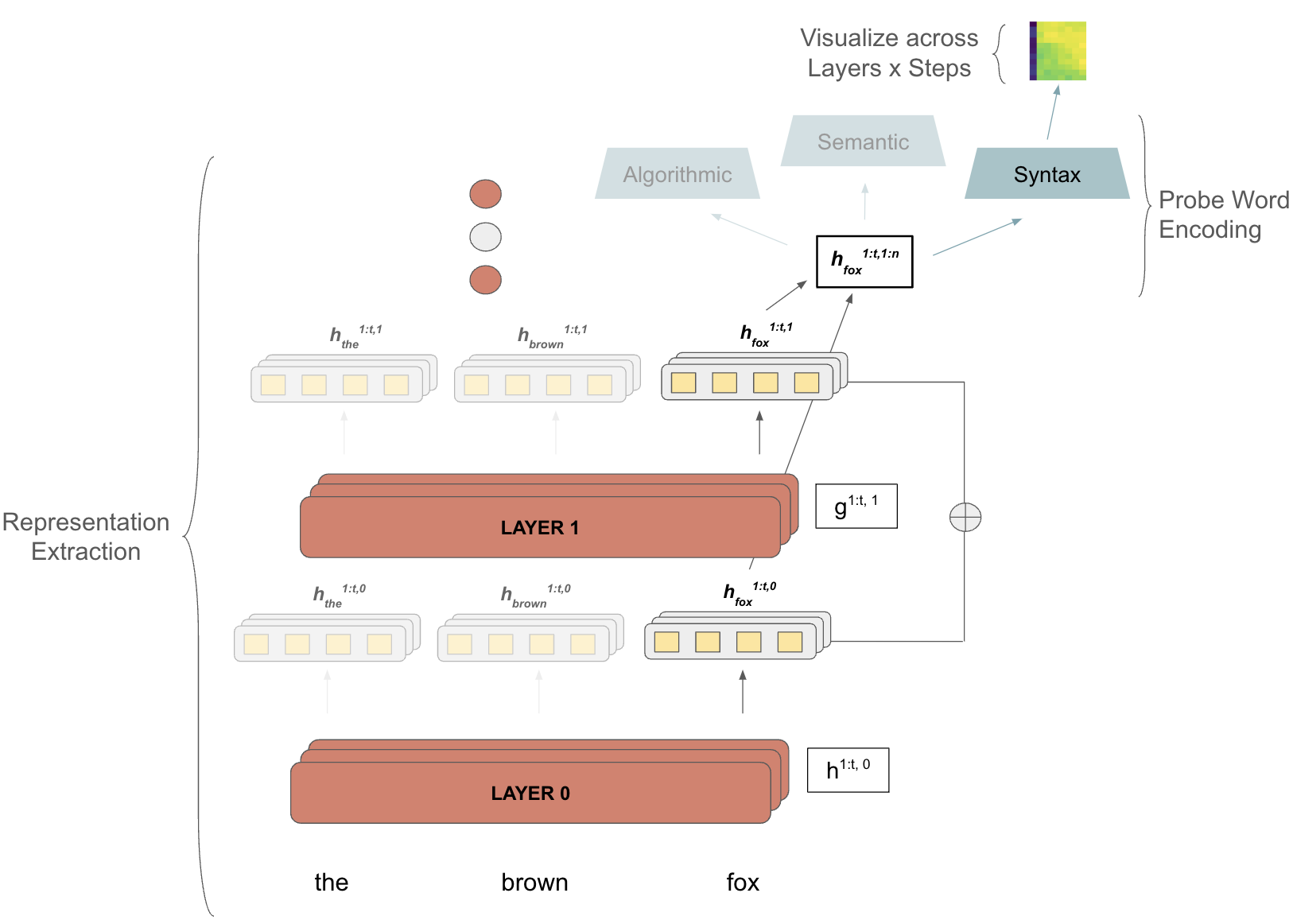

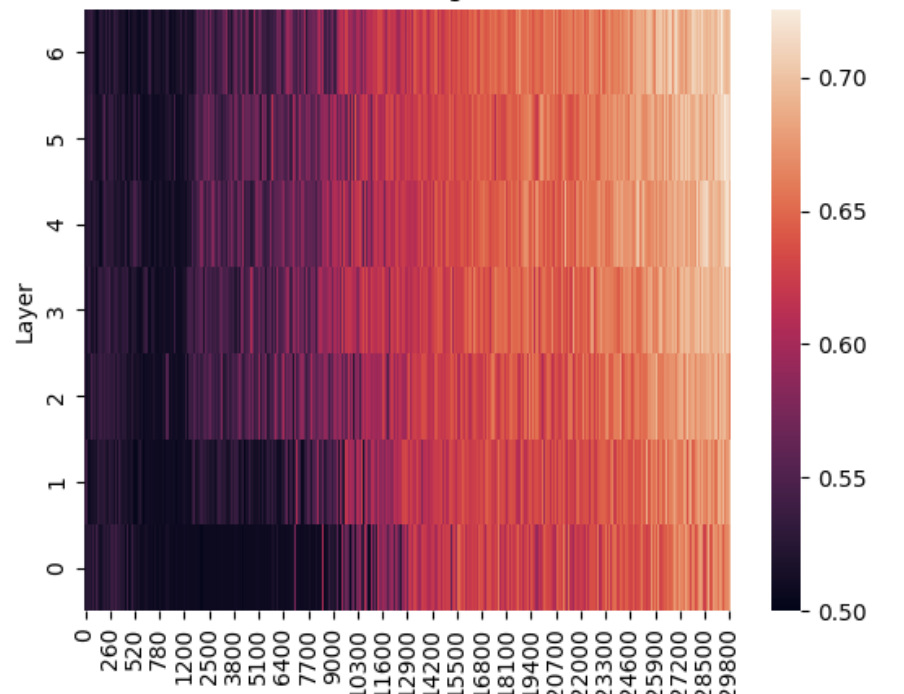

We analyzed the training dynamics of MultiBERT models using linear probing—training simple classifiers to extract syntactic information from different layers at various training checkpoints.

Syntactic Tasks Studied:

- Part-of-speech tagging (coarse and fine-grained)

- Named entity recognition

- Dependency parsing

- Phrase boundaries (start/end detection)

- Parse tree structure (depth and distance)

The Striking Pattern

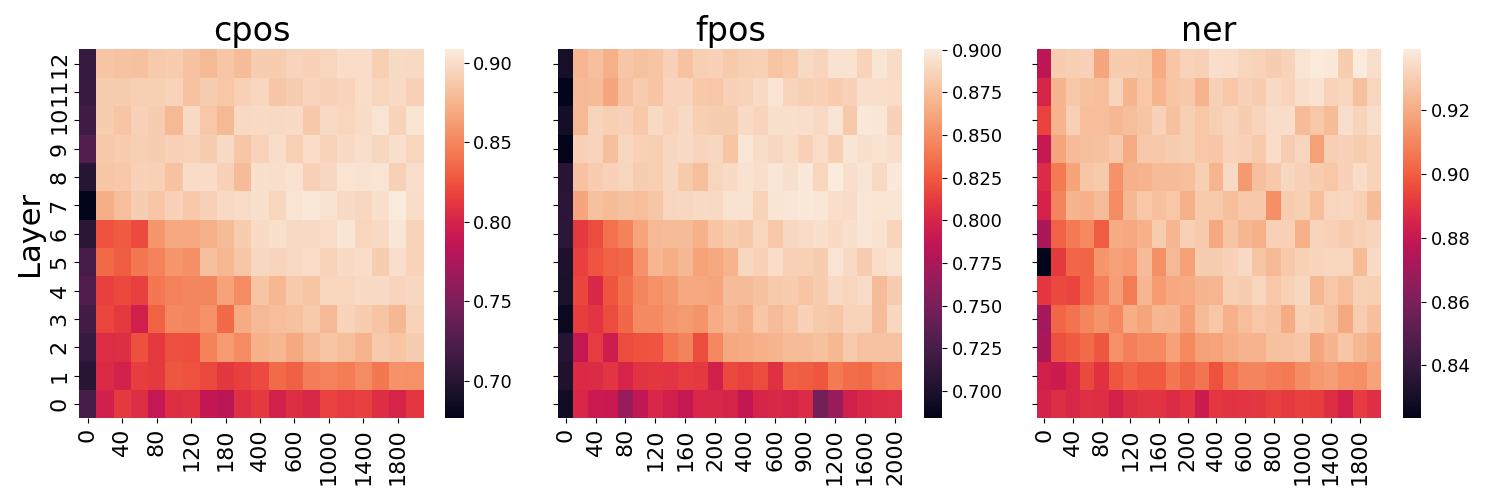

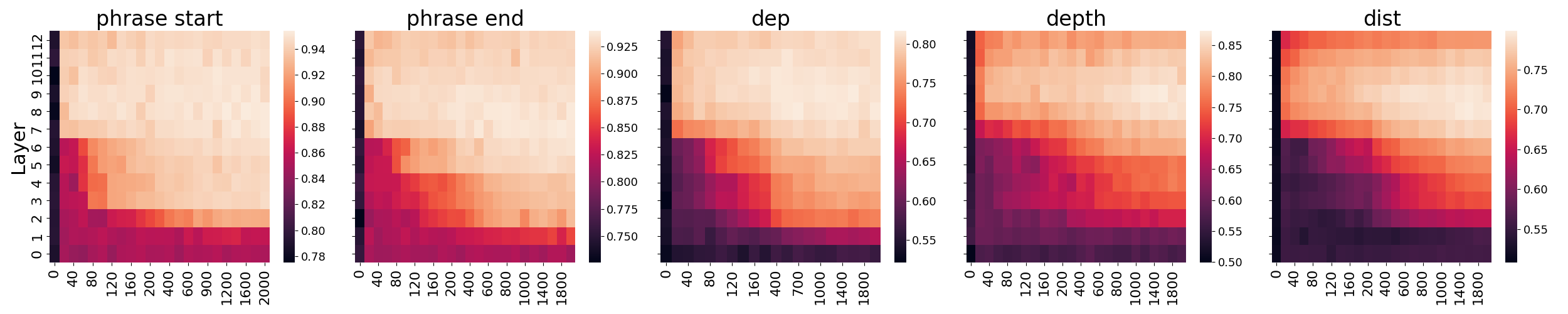

What we observed:

- Early training: Syntactic information only accessible in later layers (8-12)

- Mid training: Information becomes available in middle layers (4-8)

- Late training: Full syntactic knowledge accessible in early layers (1-3)

Two distinct regions emerged:

- Upper triangle: High accuracy, low variance (successful syntactic extraction)

- Lower triangle: Poor performance (information not yet available at that layer/time)

Task-Specific Migration Timing

Different syntactic properties “pushed down” at different rates:

Migration Order (fastest to slowest):

- Named Entity Recognition → Quick migration to early layers

- Phrase boundaries → Moderate migration speed

- Part-of-speech tagging → Steady migration

- Dependency parsing → Slower migration

- Parse tree depth/distance → Remained in deeper layers

Key Insight: Simpler syntactic properties migrated earlier, while complex structural relationships required deeper processing throughout training.

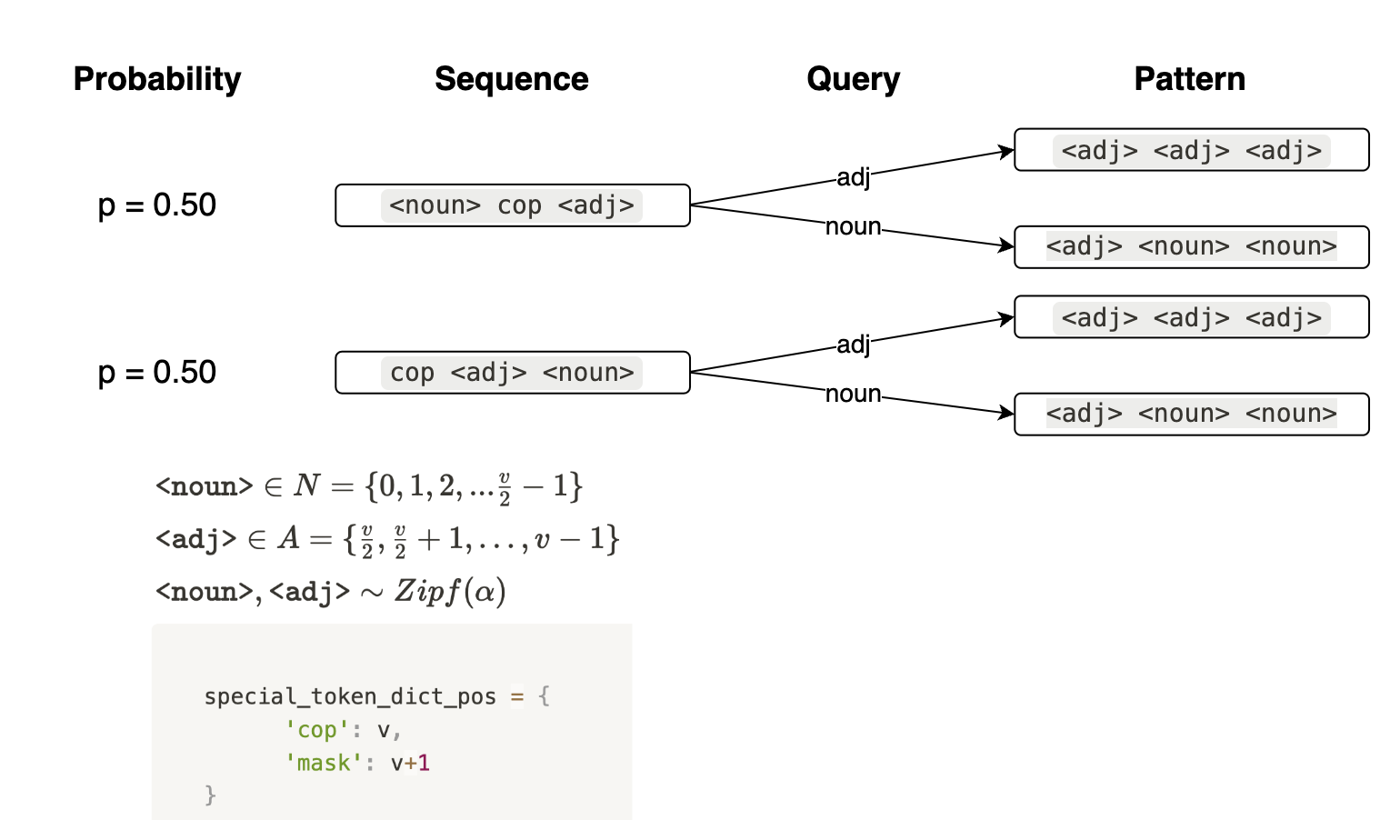

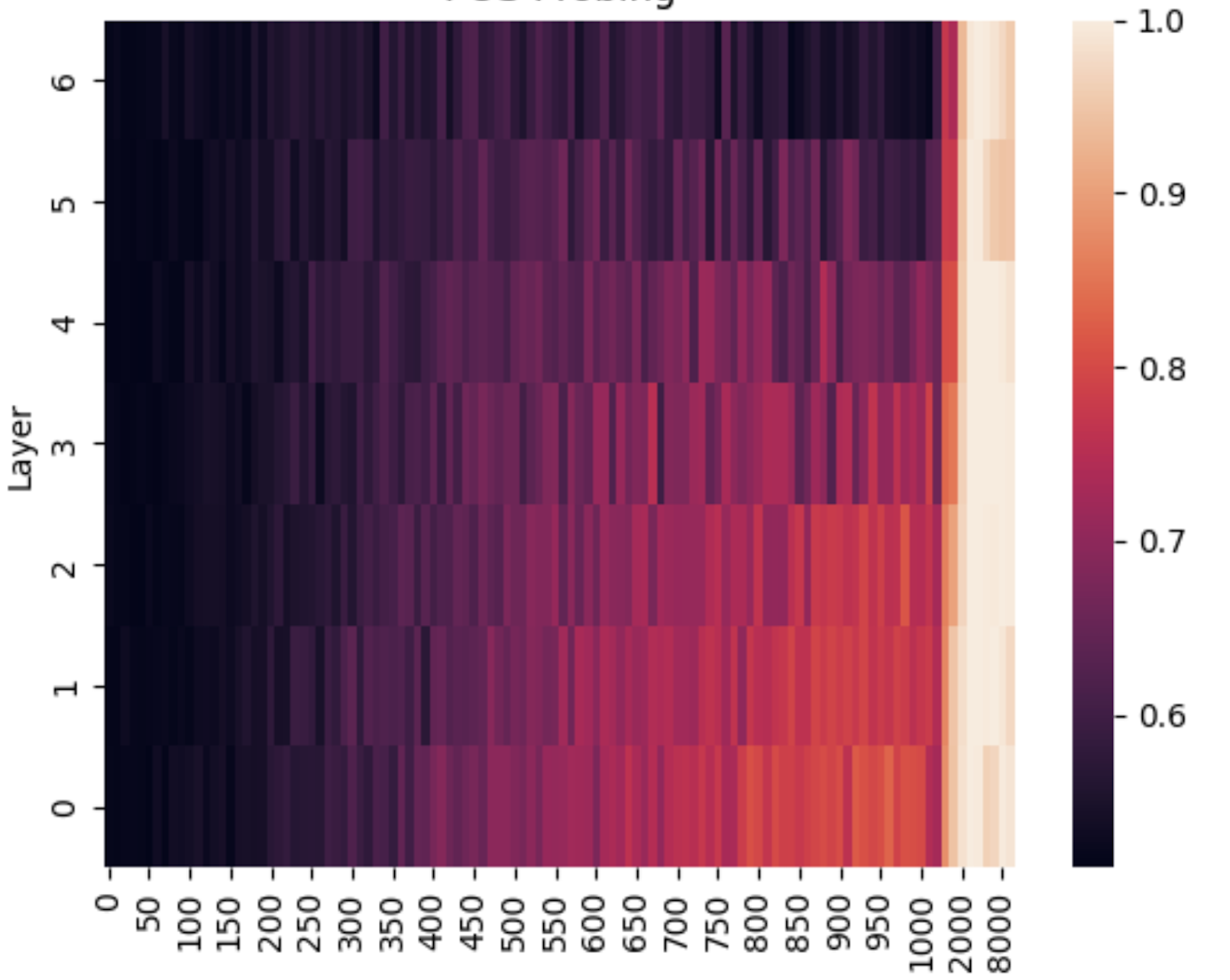

A Synthetic Setup

To understand what drives the push-down effect, we designed a controlled synthetic task that captures the essence of part-of-speech disambiguation.

Task Design

Grammar Structure:

- Sequence types:

<noun> cop <adj>orcop <adj> <noun>(50% probability each) - Query: Ask for specific

<noun>or<adj>token - Challenge: Model must determine POS of query token to generate correct pattern

Two Learning Strategies Available:

- Algorithmic: Use position relative to “cop” (copula) to determine POS

- Memorization: Encode which tokens are nouns vs. adjectives in embeddings

Critical Variables Tested

- Distribution Type: Uniform vs. Zipfian (natural language-like)

- Vocabulary Size: 100 to 20,000 tokens

- Ambiguity Level: 0% to 50% chance tokens can switch roles

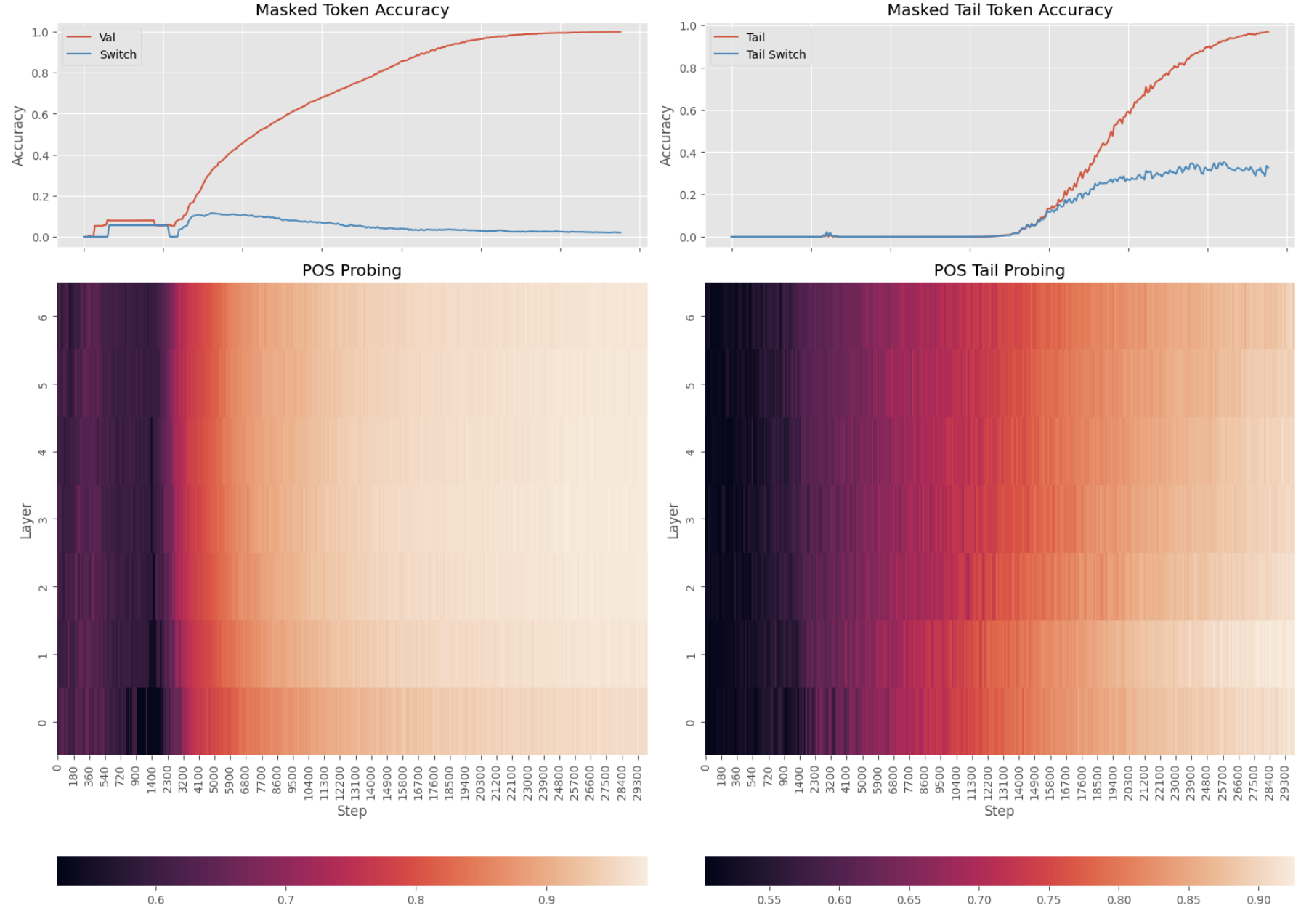

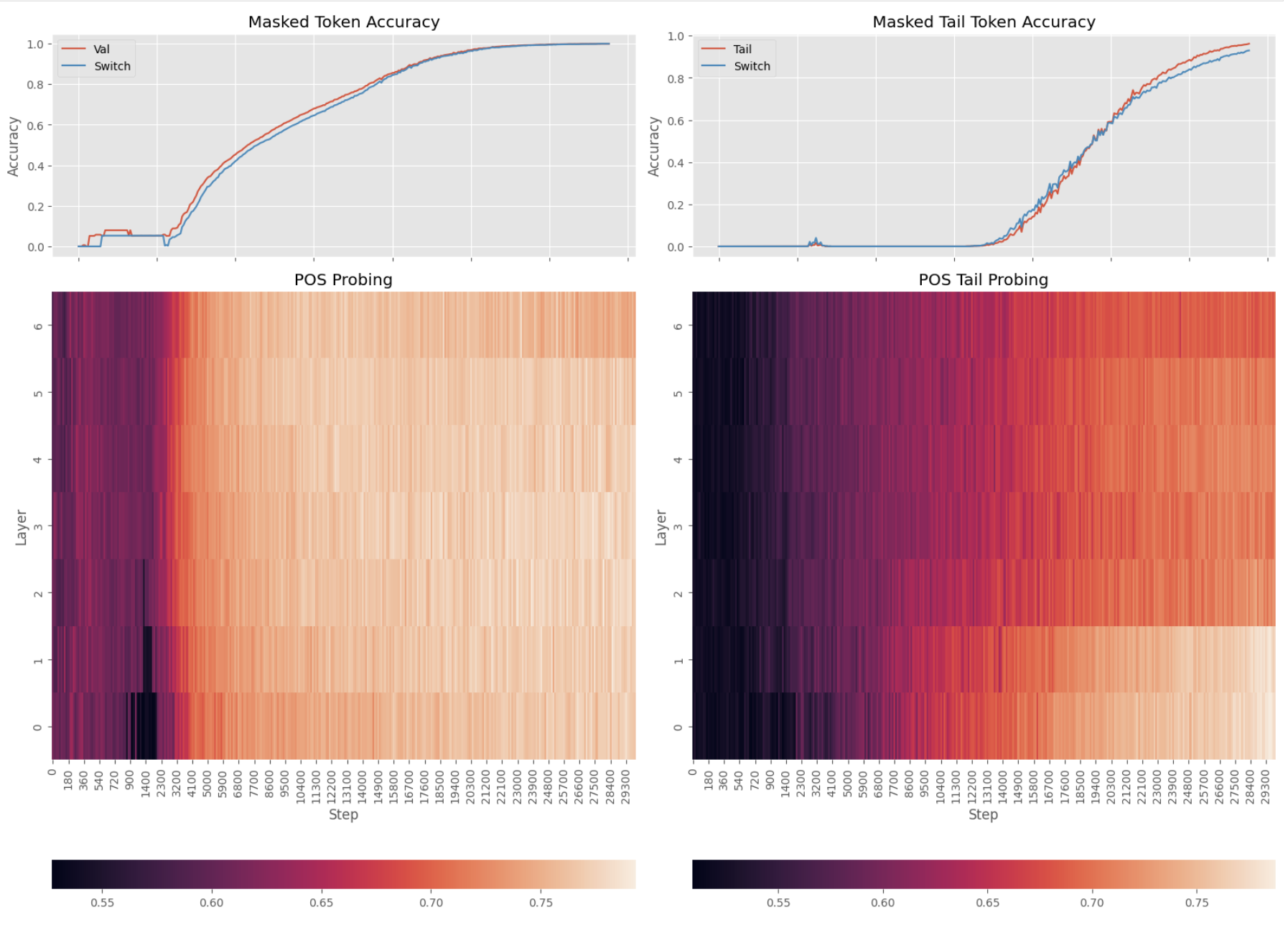

Distribution Drives Strategy Selection

Zipfian Distribution (like natural language):

- Push-down effect observed: Information migrated from late to early layers

- Strategy transition: Started with in-context learning, moved to memorization

- Critical insight: Long tail of rare words forced development of algorithmic strategy

Uniform Distribution:

- No push-down effect: Information appeared in early layers immediately

- Pure memorization: Model relied entirely on in-weights strategy

- No algorithmic development: No pressure to develop contextual reasoning

The Role of Ambiguity

No Ambiguity (0%):

- Model could rely purely on memorization

- Switch accuracy remained low (memorization successful)

Any Ambiguity (≥1%):

- Forced algorithmic strategy: Model had to use context when tokens could switch roles

- Switch accuracy matched validation accuracy: Clear evidence of in-context learning

- Surprising finding: Even with algorithmic strategy, POS information still stored in embeddings

Natural Language Statistics Drive Algorithmic Development

The Zipfian Effect: Natural language’s long-tailed distribution (many rare words) forces models to develop in-context strategies because memorization alone cannot handle the full vocabulary.

Training Progression:

- Early: Learn frequent words through memorization

- Middle: Develop algorithmic strategy for rare words

- Late: “Distill” algorithmic knowledge into early layers for efficiency

Memorization and Contextualization Coexist

False Dichotomy: The field often frames memorization vs. generalization as competing forces, but our results show they’re complementary strategies:

- Memorization: Handles frequent, unambiguous cases efficiently

- Contextualization: Handles rare and ambiguous cases accurately

- Integration: Models use both strategies simultaneously

Architecture Efficiency Through Knowledge Distillation

The Push-Down Mechanism: Later layers develop algorithmic strategies, then “teach” earlier layers to encode this knowledge more efficiently.

Computational Advantage:

- Deep processing: Available when needed for complex cases

- Shallow access: Quick lookup for common cases

- Best of both worlds: Flexibility with efficiency

Progress Measures for Strategy Detection

Novel Metrics:

- Switch Accuracy: Test model on swapped noun/adjective roles to detect algorithmic vs. memorization strategies

- Tail Accuracy: Evaluate performance on rare tokens to assess generalization

- Unseen Token Performance: Test completely novel tokens to isolate algorithmic capability

Causal Understanding: These measures allowed us to not just observe strategy changes but understand why they occurred.

Future Research

These are just initial steps. Some interesting questions that would help validate this study are here.

- Scaling to Modern Models

- Cross-Linguistic Generalization

- Applications to Model Development (e.g. Use syntactic development as training completion signal, identify when models develop problematic learning strategies)

Conclusion

Our research reveals that language models don’t simply “learn syntax”—they develop increasingly sophisticated strategies for representing and accessing syntactic information. The push-down effect demonstrates a previously unknown training dynamic where models actively reorganize their knowledge to balance computational efficiency with representational flexibility.

Key Takeaways:

- Syntactic knowledge migrates from deep to shallow layers during training

- Natural language statistics drive the development of algorithmic reasoning strategies

- Memorization and contextualization are complementary, not competing approaches

- Training dynamics provide crucial insights beyond static model analysis

Broader Impact: Understanding how models develop linguistic knowledge—rather than just what knowledge they possess—opens new avenues for building more efficient, interpretable, and robust language models.

The “push-down effect” reveals fundamental principles about how neural networks can efficiently organize knowledge, suggesting that the most effective AI systems may be those that, like our models, learn to balance multiple complementary strategies for understanding their domain.

References

Please refer to publication for references.

This research provides a developmental perspective on language model interpretability, showing that the journey of learning is as revealing as the destination. The complete experimental framework and findings offer new tools for understanding and improving language model training.