cpu-gpu-programming

from cpu optimizations to gpu kernels

From CPU Optimizations to GPU Kernels

Introduction

This blog post describes my journey through Parallel Computing on Heterogeneous (CPU + GPU) Systems at Brown University. We progress from basic CPU optimizations to advanced GPU programming, exploring the fundamental concepts that make modern high-performance computing possible. What started as simple matrix operations evolved into a deep understanding of hardware-software co-design, memory hierarchies, and parallel algorithm optimization.

Task 1: CPU Matrix-Vector Multiplication

We began with the simple task of matrix-vector multiplication. Much of the story behind this class is about maximizing performance for the given hardware. Memory access patterns and theoretical performance bounds can make or break performance.

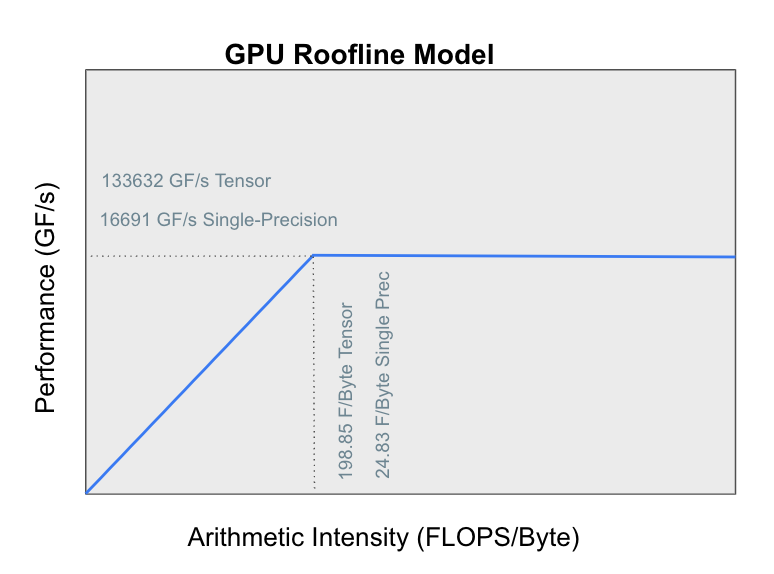

Roofline Model Analysis

Before diving into optimizations, let’s go over the roofline model, a crucial framework for understanding performance limitations. The roofline model essentially has two zones: a memory bound zone and a compute bound zone. You would like to be in the compute bound zone in order to maximally utilize your given hardware budget.

For matrix-vector multiplication:

- FLOPS: 2MN operations (one multiply, one add per element)

- Memory Access: 3 loads + 1 store per operation = 32MN bytes (assuming 8-byte doubles)

- Arithmetic Intensity: 2MN FLOPS ÷ 32MN bytes = 1/16 FLOPS/byte

This low arithmetic intensity of 0.0625 placed my algorithm firmly on the memory-bound region of the roofline model, meaning performance would be limited by memory bandwidth rather than computational capacity.

Baseline Implementation

double* performMatrixVectorMultiplication(double** matrix, double* vector, int numRowsM, int vecLength) {

double* vectorOut = new double[numRowsM];

for (int i = 0; i < numRowsM; ++i) {

vectorOut[i] = 0.0f;

for (int j = 0; j < vecLength; ++j) {

vectorOut[i] += matrix[i][j] * vector[j];

}

}

return vectorOut;

}

This naive implementation achieved an average FLOP rate of 715.598 MFLOPS across various matrix sizes, serving as my performance baseline.

Optimization 1: Contiguous Memory Layout

The first major lesson was about memory locality. Traditional 2D array allocation creates scattered memory chunks that destroy cache efficiency:

double** generateRandomMatrixContiguous(int numRows, int numCols) {

double** matrix = new double*[numRows];

matrix[0] = new double[numRows*numCols]; // Single allocation

for (int i = 1; i < numRows; i++)

matrix[i] = matrix[0] + i*numCols; // Pointer arithmetic

// ... initialization code

return matrix;

}

Surprising Result: Contiguous allocation actually slightly decreased performance to 666.975 MFLOPS. This counterintuitive result taught me that hardware behavior isn’t always predictable and that measurement is crucial.

Optimization 2: Compiler Optimizations - The Game Changer

The most dramatic improvements came from compiler optimizations:

| Optimization Level | Average FLOP Rate | Speedup |

|---|---|---|

| No optimization | 715 MFLOPS | 1.0x |

| -O1 | 941 MFLOPS | 1.3x |

| -O2 | 1,759 MFLOPS | 2.5x |

| -O3 | 1,807 MFLOPS | 2.5x |

Key Insight: The jump from -O1 to -O2 nearly doubled performance, while -O2 to -O3 showed diminishing returns. This taught me that compiler optimizations often outperform manual optimizations and that understanding what the compiler does is crucial.

Optimization 3: Manual Loop Unrolling

I implemented loop unrolling by factors of 2 and 4:

double* performMatrixVectorMultiplicationUnrolled4(double** matrix, double* vector, int numRowsM, int vecLength) {

double* vectorOut = new double[numRowsM];

for (int i = 0; i < numRowsM; ++i) {

vectorOut[i] = 0.0f;

for (int j = 0; j + 3 < vecLength; j += 4) {

vectorOut[i] += matrix[i][j] * vector[j] +

matrix[i][j+1] * vector[j+1] +

matrix[i][j+2] * vector[j+2] +

matrix[i][j+3] * vector[j+3];

}

// Handle remaining elements

for (int j; j < vecLength; j += 1) {

vectorOut[i] += matrix[i][j] * vector[j];

}

}

return vectorOut;

}

Performance Results (without compiler optimization):

- Unroll-by-2: 864.688 MFLOPS (1.2x speedup)

- Unroll-by-4: 986.188 MFLOPS (1.4x speedup)

Trade-off Discovery: Manual unrolling improved performance but made code less readable. More importantly, high compiler optimization levels often achieved better results than manual unrolling.

Task 2: Matrix-Matrix Multiplication

Matrix-matrix multiplication is the core of most deep learning and scientific computing these days. Unfortunately matrix multiplication with MN and NP matrices is 2MNP flops (N multiplications and N-1 additions per entry in the final matrix). With this O(n^3) complexity, we need more sophisticated optimization strategies. The roofline analysis revealed:

- FLOPS: 2NKM operations

- Memory Access: 3NKM loads/stores × 8 bytes = 24NKM bytes

- Arithmetic Intensity: 2NKM ÷ 24NKM = 1/12 FLOPS/byte

Still memory-bound, but slightly better than matrix-vector multiplication.

Loop Ordering Matters

One of the most surprising discoveries was how much loop order affects performance. I tested four different orderings:

// Version 1: i-j-k order (cache-unfriendly)

for (int i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

for (int j = 0; j < M; ++j) {

for (int k = 0; k < K; ++k) {

C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j]; // B accessed column-wise (non-contiguous)

}

}

}

// Version 2: i-k-j order (cache-friendly)

for (int i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

for (int k = 0; k < K; ++k) {

for (int j = 0; j < M; ++j) {

C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j]; // B accessed row-wise (contiguous)

}

}

}

Performance Comparison: | Loop Order | Average FLOP Rate | Performance Gain | |————|——————|——————| | i-j-k NMK | 0.487667 TFLOPS | Baseline | | m-n-k MNK | 0.482222 TFLOPS | -1.1% | | i-k-j NKM | 0.524519 TFLOPS | +7.5% | | k-n-m KNM | 0.524741 TFLOPS | +7.6% |

Key Insight: The i-k-j and k-n-m orders performed best because they access matrix B row-wise instead of column-wise, dramatically improving cache locality. This single change improved performance by ~7.5% without any algorithmic modifications.

Introduction to Parallel Computing with OpenMP

double** parallelMatrixMatrixMultiplication(double** C, double** A, double** B, int N, int M, int K) {

int i, j, k;

#pragma omp parallel for private(i, j, k) shared(A, B, C) collapse(2)

for (i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

for (j = 0; j < M; ++j) {

for (k = 0; k < K; ++k) {

C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j];

}

}

}

return C;

}

Breakthrough Results: OpenMP parallelization with -O0 compilation achieved ~1.001 TFLOPS, roughly doubling the baseline performance.

Key Concepts Learned:

- The

collapse(2)directive creates a larger iteration space by combining the i and j loops, enabling better load balancing across threads - Understanding shared vs. private variables is crucial for correctness

- Thread-level parallelism can dramatically improve performance even on memory-bound algorithms

Cache-Blocking Optimization: Mixed Results

double** loopBlockingMatrixMatrixMultiplication(double** C, double** A, double** B, int N, int M, int K, int blockSize) {

for (int i = 0; i < N; i += blockSize) {

for (int j = 0; j < M; j += blockSize) {

for (int k = 0; k < K; k += blockSize) {

for (int ii = i; ii < i + blockSize && ii < N; ++ii) {

for (int jj = j; jj < j + blockSize && jj < M; ++jj) {

for (int kk = k; kk < k + blockSize && kk < K; ++kk) {

C[ii][jj] += A[ii][kk] * B[kk][jj];

}

}

}

}

}

}

return C;

}

Disappointing Results:

- Block size 8: 0.469667 TFLOPS

- Block size 16: 0.499444 TFLOPS

- Block size 32: 0.459444 TFLOPS

Lesson Learned: Blocking didn’t significantly improve performance and sometimes hurt it. This taught me that not all optimizations work in all contexts, and that the overhead of nested loops can sometimes outweigh cache benefits for certain problem sizes.

Task 3: GPU Programming with CUDA

Moving from CPU to GPU programming represents a fundamental shift in thinking. Instead of optimizing for a few powerful cores, one must think about thousands of lightweight threads working in parallel on an RTX 6000 GPU. Boundary conditions are critical and everything must be thought of in terms of collective operations (e.g. all_reduce). We do this with special cuda primities such as __shfl_down_sync.

Understanding the GPU Memory Hierarchy and Roofline Model

The GPU introduces a much more complex memory hierarchy and computational model. See figure 1 for this in a basic roofline representation.

GPU Roofline Analysis:

- Peak Performance: 133632 GF/s (Tensor), 16691 GF/s (Single-Precision)

- Memory Bandwidth: ~760 GB/s

- Arithmetic Intensity: Still 1/24 FLOPS/byte (memory-bound)

The dramatically higher computational capacity meant that memory optimization would be even more critical.

Thread Organization: Understanding Warps, Blocks, and Grids

#define WARP_SIZE 32

#define FULL_MASK 0xffffffff

Key Concept: GPU threads are organized hierarchically:

- Threads execute in groups of 32 called warps

- Warps execute in lockstep (SIMT - Single Instruction, Multiple Thread)

- Blocks contain multiple warps and share fast shared memory

- Grids contain multiple blocks distributed across the GPU

Baseline Implementation: One Thread Per Row

__global__

void mvKernelNoWarp(double* matrix, double* vector,

int numRowsM, int vecLength,

double* result) {

int row = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x * blockDim.x;

if (row < numRowsM) {

for (int col = 0; col < vecLength; col ++) {

if (col < vecLength) {

result[row] += matrix[row*vecLength + col] * vector[col];

}

}

}

}

Baseline Performance: 0.000298438 TFLOPS - disappointing compared to CPU implementations.

Problem: This approach doesn’t leverage the GPU’s parallel execution model effectively. Each thread does sequential work, similar to CPU programming.

Optimization 1: Single Warp Per Row - Learning Warp-Level Programming

__global__

void mvKernelSingleWarp(double* matrix, double* vector,

int numRowsM, int vecLength,

double* result) {

int row = blockIdx.x;

int lane = (threadIdx.x) % WARP_SIZE;

double sum = 0.0;

if (row < numRowsM) {

// Each thread in the warp handles different columns

for (int col = lane; col < vecLength; col += WARP_SIZE) {

if (col < vecLength) {

sum += matrix[row*vecLength + col] * vector[col];

}

}

__syncwarp();

// Warp reduction using shuffle instructions

for (int offset = WARP_SIZE/2; offset > 0; offset /= 2) {

sum += __shfl_down_sync(FULL_MASK, sum, offset);

}

if (lane == 0) {

result[row] = sum;

}

}

}

Performance: 0.000346125 TFLOPS (slight improvement)

Breakthrough Concept: The __shfl_down_sync instruction is a warp-level primitive that allows threads within a warp to exchange data without using shared memory. This tree-reduction pattern:

- Thread 0 gets sum from thread 16

- Thread 0 gets sum from thread 8

- Thread 0 gets sum from thread 4

- Thread 0 gets sum from thread 2

- Thread 0 gets sum from thread 1

In just 5 steps, we reduce 32 partial sums to a single result!

Optimization 2: Multiple Warps Per Row - Hierarchical Reduction

__global__

void mvKernelMultipleWarps(double* matrix, double* vector,

int numRowsM, int vecLength,

double* result) {

int row = blockIdx.x;

int lane = threadIdx.x % WARP_SIZE;

int warpid = threadIdx.x/WARP_SIZE;

int nwarps = blockDim.x/WARP_SIZE;

double sum = 0.0;

if (row < numRowsM) {

// Distribute work across multiple warps

for (int col = lane + WARP_SIZE*warpid; col < vecLength; col += WARP_SIZE*nwarps) {

if (col < vecLength) {

sum += matrix[row*vecLength + col] * vector[col];

}

}

__syncwarp();

// Intra-warp reduction

for (int offset = WARP_SIZE/2; offset > 0; offset /= 2) {

sum += __shfl_down_sync(FULL_MASK, sum, offset);

}

__shared__ double s_mem[1024/WARP_SIZE]; // max 32 warps per block

if (lane == 0) {

s_mem[warpid] = sum;

}

__syncthreads(); // sync threads within block

if (threadIdx.x == 0) { // first lane in first warp

for (int j = 0; j < nwarps; ++j) {

result[row] += s_mem[j];

}

}

}

}

Dramatic Performance Improvement: 0.00972644 TFLOPS with 32 warps per row - a 32x improvement over the baseline!

Advanced Concepts Learned:

- Hierarchical Reduction: First reduce within warps using shuffle instructions, then across warps using shared memory

- Memory Coalescing: Threads in a warp access contiguous memory locations (lane + WARP_SIZE*warpid ensures proper stride)

- Shared Memory: Fast on-chip memory shared by threads in the same block

- Synchronization:

__syncwarp()for intra-warp sync,__syncthreads()for intra-block sync

Performance Scaling Analysis

The performance gains were heavily dependent on matrix dimensions:

| Matrix Size | No Warp | Single Warp | Multiple Warps (32) | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10×10 | 4e-06 | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| 100×100 | 4.5e-05 | 4.6e-05 | 0.000333 | 7.4x |

| 1000×1000 | 0.000237 | 0.000294 | 0.003174 | 13.4x |

| 10000×10000 | 0.000389 | 0.000704 | 0.03125 | 80.3x |

Key Insight: GPU performance scales dramatically with problem size. Small problems don’t have enough parallelism to saturate the GPU, while large problems can achieve spectacular speedups.

Special Case: Many Columns, Few Rows

For matrices with many columns but few rows (e.g., 10×10000), the multiple warps strategy achieved 0.018181 TFLOPS - a 171x improvement over the baseline 0.000106 TFLOPS. This scenario is ideal for GPU parallelization because each row has enough work to keep many threads busy.

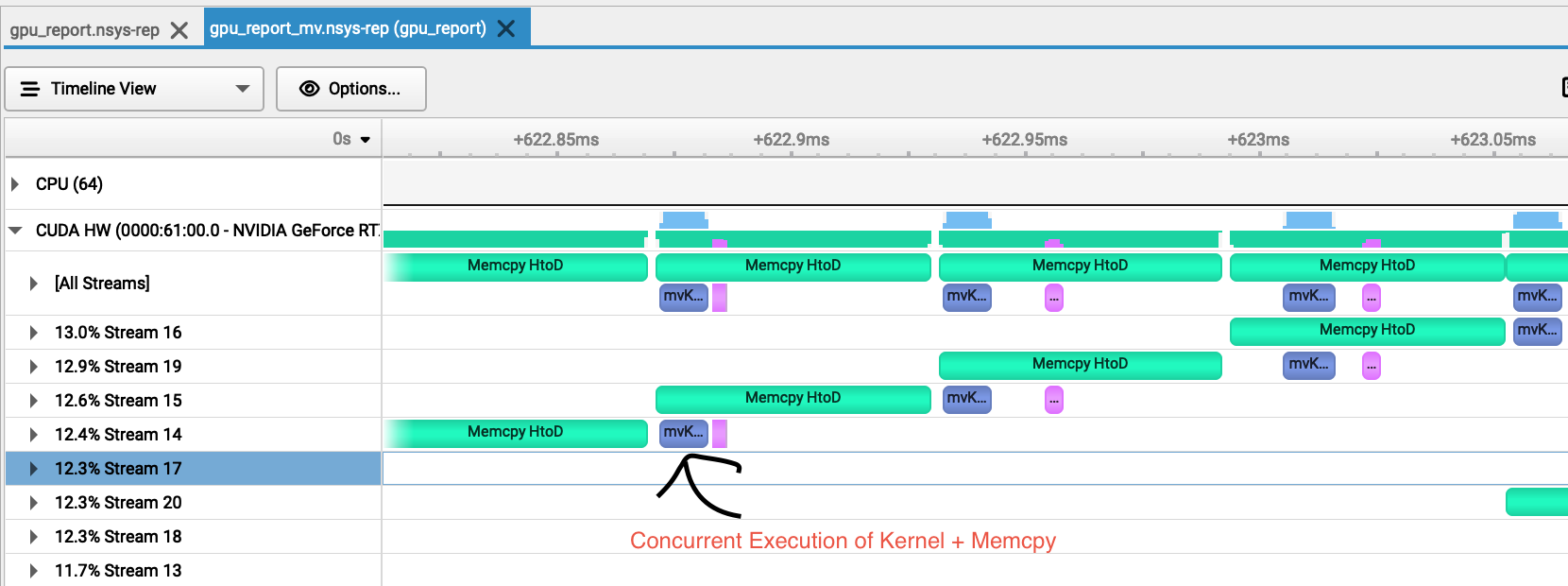

Task 4: CUDA Streams

The final task introduced sophisticated execution strategies needed for production GPU code, focusing on concurrent execution and memory transfer optimization.

Baseline: Single Stream Performance

Using the optimized multiple-warps kernel from task 3 as a baseline:

| Matrix Size | Time (μs) | FLOP Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 1000×1000 | 7,132 | 0.000338 TFLOPS |

| 1500×1500 | 7,004 | 0.000512 TFLOPS |

| 2000×2000 | 7,341 | 0.001012 TFLOPS |

Baseline Average: 0.000620 TFLOPS

CUDA Streams: Overlapping Computation and Communication

void matVecMul(double* mat_h, double* vec_h, double* result_h, int M, int numRowsM, int vecLength) {

double *mat_d, *vec_d, *result_d;

cudaMalloc(&mat_d, numRowsM * vecLength * sizeof(double));

cudaMalloc(&vec_d, vecLength * sizeof(double));

cudaMalloc(&result_d, numRowsM * sizeof(double));

int streamNumRows = (numRowsM + M - 1)/M; // ceil division

cudaStream_t streams[M];

// Create multiple streams for concurrent execution

for (int i = 0; i < M; i++) {

cudaStreamCreate(&streams[i]);

}

// Launch kernels on different streams

for (int i = 0; i < M; i++) {

mvKernelMultipleWarps<<<nblocks, nthreads, 0, streams[i]>>>(

mat_d + i * streamNumRows * vecLength,

vec_d,

numRowsM, vecLength, i, streamNumRows,

result_d + i * streamNumRows

);

}

// Synchronize and cleanup

for (int i = 0; i < M; i++) {

cudaStreamSynchronize(streams[i]);

cudaStreamDestroy(streams[i]);

}

}

Stream Performance Analysis

Performance Results with Multiple Streams:

| Matrix Size | Streams | Time (μs) | FLOP Rate | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000×1000 | 1 | 7,132 | 0.000338 | Baseline |

| 2 | 7,609 | 0.000262 | -22.5% | |

| 3 | 2,451 | 0.000815 | +141% | |

| 4 | 2,474 | 0.000808 | +139% | |

| 7 | 2,426 | 0.000824 | +144% | |

| 1500×1500 | 1 | 7,004 | 0.000512 | Baseline |

| 2 | 3,796 | 0.001185 | +131% | |

| 8 | 3,727 | 0.001207 | +136% | |

| 2000×2000 | 1 | 7,341 | 0.001012 | Baseline |

| 3 | 5,316 | 0.001504 | +49% | |

| 4 | 4,829 | 0.001656 | +64% |

Overall Average: 0.000956 TFLOPS - a 54% improvement over single-stream execution.

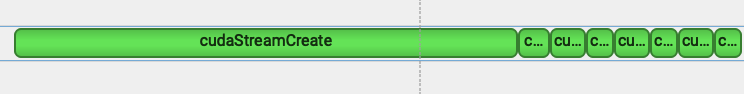

Critical Discovery: Stream Creation Overhead

Stream Creation Timing Analysis:

- 1 stream: 17 μs average

- 2 streams: 21 μs average

- 3 streams: 23 μs average

- 8 streams: 33 μs average

Key Findings:

- Non-linear scaling: Stream creation overhead doesn’t scale linearly

- First stream penalty: Creating the first stream takes much longer than subsequent streams

- Diminishing returns: Performance plateaued after ~3 streams

Memory Transfer Bottleneck Discovery

Through profiling analysis, I discovered that memory allocation and transfer operations took significantly longer than the actual computation. The total matrix-vector multiplication averaged only 11.00800 μs, while memory operations dominated the execution time.

Profiler Insights:

- Kernel execution and result vector copying happened concurrently across multiple streams

- Memory transfers from host to device were optimized by the NVIDIA driver to avoid redundant copies

- The concurrent execution pattern showed clear overlap between computation and communication

Pinned Memory Optimization

All host memory was allocated using cudaHostAlloc for page-locked (pinned) memory, which enables:

- Faster transfers: Pinned memory can be transferred via DMA without CPU involvement

- Concurrent execution: Allows overlap of memory transfers with kernel execution

- Predictable performance: Eliminates page faults during transfers

I was fairly surprised with how quickly the effect of stream concurrency leveled out. Additionally, it was interesting how much longer memory allocation/copying took than the matrix vector calculation. I think the best way to optimize the program going forward would be to optimize the memory allocation/freeing/copying, as that seems to create the heaviest burden computationally

–

Summary

1. Performance Analysis Frameworks

- Roofline Model: Understanding the theoretical performance bounds imposed by arithmetic intensity

- Memory Hierarchy Optimization: Cache behavior, memory access patterns, and bandwidth limitations

- Profiling and Measurement: Using timing instrumentation and GPU profilers to identify bottlenecks

2. Parallel Algorithm Design Principles

- Decomposition Strategies: How to break problems into parallel components

- Load Balancing: Ensuring work is distributed evenly across processing units

- Synchronization: Managing dependencies and data races in parallel execution

- Scalability: Understanding how performance changes with problem size and hardware resources

3. Hardware-Software Co-design

- CPU Optimizations: Cache-friendly algorithms, compiler optimizations, instruction-level parallelism

- GPU Architecture: Warp-based execution, memory coalescing, hierarchical memory systems

- Memory Management: Pinned memory, concurrent transfers, stream scheduling

4. Advanced GPU Programming Patterns

- Warp-level Programming: Using shuffle instructions for efficient intra-warp communication

- Hierarchical Reduction: Combining warp-level and block-level reduction strategies

- Stream Programming: Overlapping computation with communication for better resource utilization

Tools and Techniques

Here are some of the tools and the techniques that I used for these experiments.

Development and Profiling Tools

- CUDA Toolkit: GPU programming, debugging, and optimization

- NVIDIA Nsight: Advanced GPU profiling and performance analysis

- OpenMP: CPU parallelization and thread management

- GCC Optimization Flags: Understanding compiler behavior and optimization levels

- SLURM: High-performance computing job scheduling and resource management

Programming Patterns and Algorithms

- Reduction Operations: Tree-based algorithms for combining distributed results

- Memory Coalescing: Optimizing memory access patterns for GPU efficiency

- Warp-level Programming: Leveraging GPU architectural features for performance

- Stream Programming: Concurrent execution and resource scheduling

- Cache-blocking: Optimizing for memory hierarchy behavior

Conclusion

The progression from basic CPU optimizations to advanced GPU programming represents more than just a technical journey—it’s a fundamental transformation in computational thinking. Each task built systematically upon the previous, creating a comprehensive understanding of modern parallel computing systems.

Most Valuable Insights:

-

Performance is multidimensional: It’s not just about faster algorithms, but about understanding the complex interplay between hardware architecture, memory systems, and algorithmic design.

-

Optimization requires systematic methodology: The combination of theoretical analysis (roofline models), empirical measurement (profiling), and iterative refinement proved essential for achieving significant performance gains.

-

Parallel programming demands new mental models: Moving from sequential to parallel thinking required learning about synchronization, load balancing, memory coherence, and hierarchical algorithm design.

-

Hardware evolution drives software innovation: As computing systems become more parallel and heterogeneous, understanding multiple programming models and optimization strategies becomes increasingly critical.

The 668x performance improvement from the initial CPU implementation to the final GPU+streams version demonstrates the transformative power of parallel computing. However, the real value lies not in the speedup numbers, but in developing the analytical skills, debugging methodologies, and architectural understanding needed to tackle future computational challenges.

As computing continues to evolve toward exascale systems, quantum computers, and neuromorphic processors, the fundamental principles I believe will stay the same—understanding hardware, measuring performance, thinking in parallel, and designing for scalability—will remain the essential foundation for pushing the boundaries of what’s computationally possible.

This blog post describes my learning journey through APMA2822 at Brown University. The complete code implementations, experimental data, and profiling results are available in the course repository. Disclosure: Parts of this blog post were written w/ Claude so please email me at firstnamek610 at gmail